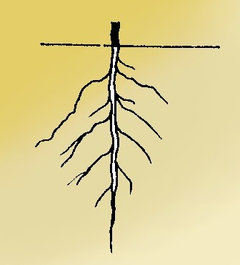

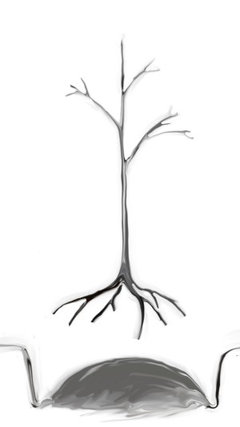

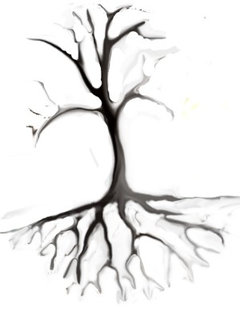

What to do with taproot when you transplant a tree?

edlincoln

8 years ago

Featured Answer

Sort by:Oldest

Comments (54)

edlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agosam_md

8 years agoRelated Discussions

When do you transplant?

Comments (5)Nan, I wouldn't move sambucus now for one and simple reason, right now you don't know what winter'06 will be and if it will be as severe as '04, it may die to the ground. Healthy established root system of the early spring transpalnt will guarantee you a normal growing season even if you have to cut it to the ground. By moving now you'll set root system back (though it still have some time to adjast, but nevertheless, not to the full extend) and if winter will be severe, underground system might be not substantial to produce/support a lot of growth. Cultural wise, Bonica rose could be moved either in mid-late November or in a spring, really doesn't matter. My personal preference for moving roses is November, when you already could cut them with no worry about regrowths, they are already dormant or semi-dormant, grounds are workable and you still have a clear memories/visions of what was where and how it would work next year. Also, by moving them in a spring you might be a little bid late, feeder roots already start growing and inevitably you'll damage some of them, thus setting plant back. Not crucial with roses, but I still prefer fall over the spring. Bonica in particular is a very tuff and vigorous cookie, so leave it at least 5' space. I don't know if you know, but Bonica can produce long arching canes that could be easily pegged and if covered by soil will self-root easily. In a 3-4 year it could form an unpenetratable colony if you wish to treat it in a such way....See MoreWhat do you use when treating pests on your trees?

Comments (6)the only time i ever used any type of insect control was when i was first starting my cutting 4yrs ago and had some spider mites on the young trees in the house. i had used neem oil aka; All Season Oil. since then i have never had to apply anything else as i have never noticed any insects on the trees. my trees are grown in large pots and placed in a unheated garage during the winter....See MoreWhat to do with fungus gnats when transplanting

Comments (8)Absolutely no worries when the plants are moved outside :-) First, there are all manner of predators that will make short work of gnats and second, the ground soil will not have the same high organic content or moisture levels as does the potting soil so not encouraging to gnat development. And to be perfectly honest, fungus gnats are more of a nuisance or irritant and an indication of poor water movement (which can affect plant health) than they are actually harmful to the plants themselves....See MoreDo you unplug your tree when you leave the house if you have pets?

Comments (26)Over 50 years ago, my parents had a cat. Every Christmas, we would find Mehitabel (yes, named for the famous cat in the book, Archie and Mehitabel) sitting on a sturdy branch, right up against the trunk of the tree, staring at us like the Cheshire cat. Now this was a tree with that old-fashioned tinsel put on it, lovingly one or two pieces at a time (it took forever!), and not one strand was out of place. We never saw Mehitabel get up in the tree, nor did we ever witness her descent. She looked quite lovely with her eyes "glowing" from the tree lights! She was quite a character. None of our cats ever got up IN the tree, but they did knock it over during the night one time (nasty old-style Christmas tree stand). We tied it to something from then on and never again heard that unmistakable sound in the middle of the night....See Moregardengal48 (PNW Z8/9)

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agoUser

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agobossyvossy

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agogardengal48 (PNW Z8/9)

8 years agoToronado3800 Zone 6 St Louis

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agoUser

8 years agobossyvossy

8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agoUser

8 years agogardener365

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agogardener365

8 years agogardener365

8 years agoUser

8 years agoUser

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agoUser

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agoUser

8 years agoedlincoln

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agorhizo_1 (North AL) zone 7

8 years agosam_md

8 years agorhizo_1 (North AL) zone 7

8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agobrandon7 TN_zone7

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agotete_a_tete

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agoUser

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agobengz6westmd

8 years agolast modified: 8 years ago

Related Stories

PLANTING IDEASStretch the Budget, Seasons and Style: Add Conifers to Your Containers

Small, low-maintenance conifers are a boon for mixed containers — and you can transplant them to your garden when they’ve outgrown the pot

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESPlant Black Cherry Trees for the Birds and Bees

Plant Prunus serotina in the Central and Eastern U.S. for spring flowers, interesting bark and beautiful fall color

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDES8 Essential Native Shade Trees for the U.S. Southeast

These beauties provide cool shade in the summer and easily withstand the heat and humidity of the South

Full Story

LANDSCAPE DESIGNThe Unparalleled Power of Trees

Discover the beauty and magic of trees, and why a landscape without them just isn't the same

Full Story

WINTER GARDENINGHow to Help Your Trees Weather a Storm

Seeing trees safely through winter storms means choosing the right species, siting them carefully and paying attention during the tempests

Full Story

WINTER GARDENINGExtend Your Growing Season With a Cold Frame in the Garden

If the sun's shining, it might be time to sow seeds under glass to transplant or harvest

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDES5 Best-Behaved Trees to Grace a Patio

Big enough for shade but small enough for easy care, these amiable trees mind their manners in a modest outdoor space

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESPalm Trees Take Interiors on a Tropical Vacation

Conjure a sultry vibe or bring welcome life to modern rooms. Whatever your interior design style, palm trees are the ticket to enhancing it

Full Story

CHRISTMASReal vs. Fake: How to Choose the Right Christmas Tree

Pitting flexibility and ease against cost and the environment can leave anyone flummoxed. This Christmas tree breakdown can help

Full Story

FALL GARDENING6 Trees You'll Fall For

Don’t put down that spade! Autumn is the perfect time for planting these trees

Full Story

rhizo_1 (North AL) zone 7