A long read for Halloween ... (David Sedaris)

IdaClaire

8 years ago

Featured Answer

Sort by:Oldest

Comments (14)

hhireno

8 years agoIdaClaire

8 years agoRelated Discussions

NEW: obf: october's happy halloween

Comments (107)Happy Day after Halloween!! So sorry I was MIA for the last couple of days. Unexpected family thingy's going on...and of course, HALLOWEEN!! My 2 dinosaurs sure kept me on my feet yesterday that's for sure :) I hope everyone had a wonderful Halloween! I may take a couple of days to recover. But, its so nice out today, I better get outside and take down all my decorations. We have graveyards, archways, ghosts, and skeletons...everywhere!!! It will take all day to pack it up...then on to turkeys and haybales for Thanksgiving :) Shirley, Is bear poop lucky?? I heard an old wivestale that if a bird poops on you its lucky...does the same go for bear? :) I can only imagine how much you had to wash off...ewwwww My mom loves books on tape, and gets them from our library too. My husband just started listening to them when he's in the truck, he really enjoys them. Our library has a used book sale a couple of times a year and they always have books on tape too. I got some for my mom for 50cents each. Jeanne, Congratulations on your new family member! Sydney is a very lucky pooch! :) Margo, I'm glad your little one is starting to feel better. :) Bunny, the garlic is from the garden. You can eat some and plant some if you'd like. It comes back every year, and if you cook with it, its way cheaper to grow your own. :) HAPPY HALLOWEENS ON THE WAY! Michelle (micyrey) sends to Jen (jlee160)***SENT***REC'D*** Jen (jlee160) sends to Margo (smitties)***SENT***REC'D*** Jeanne (sandlapper_rose) sends to Annie (canyonwind)***SENT***REC'D*** Rose (rosemctier) sends to Michelle (micyrey)***SENT***REC'D*** Melissa (hazelnutbunny) sends to Beth (beth_b_kodiak)***SENT***REC'D*** Margo (smitties) sends to Shirley (brittneysgran)***SENT***REC'D*** Beth (beth_b_kodiak) sends to ME (mellen)***SENT***REC'D*** Shirley (brittneysgran) sends to Rose (rosemctier)***SENT***REC'D*** Vina (flowergirl34) sends to Melissa (hazelnutbunny)***SENT***REC'D*** ME (mellen) sends to Jeanne (sandlapper_rose)***SENT***REC'D*** Annie (canyonwind) sends to Vina (flowergirl34)***SENT***REC'D*** I happily declare this swap officially closed. Thank you very much ladies for making this truly a HAPPY HALLOWEEN! Now onto November...Jeanne...take it away... vina...See MoreDo you 'do' Halloween?

Comments (53)I love Halloween also, but we don't get any children. We also have a house in a wooded neighborhood with 3 acre lots. But I still buy candy every year and hope. We decorate for ourselves nevertheless. I have all sorts of things I do throughout the house and outside. I just ordered this Snoopy in the pumpkin patch. He won't even go in the front since nobody comes by - he'll go out back just beyond the deck where we can see him lit up every night! I'll of course have to do hay stacks and many pumpkins all around him! I do think we might do a bonfire this year on Friday the 26th, which is the full Hunter's Moon. Sort of a work celebration for a project that's winding down in a couple of weeks. Was thinking of hot dogs of course and smores and such, but also having caramel apples and popcorn balls and making the back yard look really great for the occasion. Does anyone do anything for dia de los muertos, or Day of the Dead on the 1st. After watching the Showtime series Dead Like Me and being TOTALLY crazed fans of Mandy Patinkin, I'm curious about doing some fun day of the dead thing....See MoreDarling buds of May: reading

Comments (67)Just finished Everything Under the Sky by Matilde Asensi. Set in the 1930's, a Parisian woman (who was born in Spain) heads to China to tidy up the affairs of her recently-deceased and long-estranged husband. When she arrives she finds things are not as she suspected. Her late husband collected Chinese artifacts and one of them is extremely important in Chinese history. Unfortunately, to settle her late husband's debts, she must embark on a journey to solve the riddle of this artifact and hope to find the treasure at the end. But the bad guys want the treasure, too. It reads like an Indiana Jones/American Treasure movie set in China. The author explains a lot of the Chinese philosophy in depth: the I Ching, Five Elements, Feng Shui, Taoism, martial arts and so on. It is also laced with long paragraphs of Chinese history. I personally loved the philosophy and history in the book. As a martial artist and martial arts instructor, I enjoyed seeing the main character "on the path" although she had no idea she was on it. PAM...See MoreSeptember: sweet corn, stormy skies, school bells. Your readings?

Comments (66)Georgia - happy to see someone else reading "The Moonflower Vine"... It was a title I found somewhere and dug up and enjoyed. I've been reading (and reminding myself) how to write by reading "On Writing Well" by William Zinsser. A book straight out of the late 1970's, Zinsser was/is? a prof at Yale and has a journalist's background. It's more of a primer than anything, but he has a good sense of humor and I've finally learned the plural of "genius" is "genii". And then speaking of well written, I am also reading and enjoying "Consuming Passions: Leisure and Pleasure in Victorian Britain" by Judith Flanders which is *packed* with detail about this time. Obsessed with Victorians as I seem to be, this is a great read and I'm having fun. However, it suffers from a steady stream of typos which is a bit distracting. Speaking of distracting, I am also reading "Skippy Dies" by Paul Murray about a death in an Irish boarding school. Light hearted and the writing is fine, but whoever decided to "translate" all the English/Irish bits into "American" needs to smothered. "Mum" or "Mam" is now "Mom". "Shopping Center" is now "mall" and numerous other examples. Unless things have been decidedly American in my long absence from living in UK?... All good reads if you're not too pedantic about stuff other than the story. (The pains of being an editor.) :-)...See MoreUser

8 years agoUser

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agoOlychick

8 years agoterezosa / terriks

8 years agoBluebell66

8 years agohhireno

8 years agoIdaClaire

8 years agolast modified: 8 years agogramarows

8 years agoUser

8 years agoOlychick

8 years agoOlychick

8 years ago

Related Stories

MOST POPULARBewitching Halloween Entryways by Houzzers

Clever, crafty or downright creepy, these outdoor and window decorations by Houzzers cast a spell all their own

Full Story

OUTDOOR ACCESSORIESGuardians of the Gate

Dog statues have long been used to adorn a home’s exterior, and man’s best friend usually has a message, too

Full Story

RANCH HOMESHouzz Tour: An Eclectic Ranch Revival in Washington, D.C.

Well-considered renovations, clever art and treasures from family make their mark on an architect’s never-ending work in progress

Full Story

DENS AND LIBRARIESHow to Care for Your Home Library

Increase your enjoyment of books with these ideas for storing, stacking and displaying them

Full Story

DECORATING GUIDESFlea Market Finds: Demijohns Around the Home

Once purely functional, now decorative, these bottles are worth the hunt

Full Story

KITCHEN DESIGN10 Smashing Black Kitchens

Looking for something different from an all-white kitchen? Think about going stylishly dark instead

Full Story

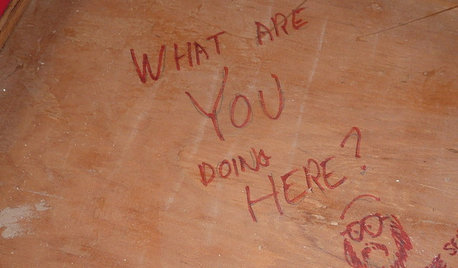

FUN HOUZZDoes Your Home Have a Hidden Message?

If you have ever left or found a message during a construction project, we want to see it!

Full Story

HOLIDAYSCollecting Christmas Ornaments That Speak to the Heart

Crafted by hand, bought on vacation or even dug out of the discount bin, ornaments can make for a special holiday tradition

Full Story

HOLIDAYSThese Homes Say Happy Mardi Gras!

Let the good times roll around the house with Mardi Gras beads, glittery high heels, Fat Tuesday colors and more

Full Story

HOUZZ TOURSHouzz Tour: Farm Fresh

Updates bring back the bygone charm of a 19th-century Texas farmhouse, while making it work for a family of 6

Full StorySponsored

busybee3