NY Times "The Kitchen as a Pollution Hazard"

deeageaux

10 years ago

Featured Answer

Sort by:Oldest

Comments (20)

jwvideo

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agokaseki

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agoRelated Discussions

NY Times essay - Kitchens as health hazard?

Comments (21)We are rather extreme about our food. We eat mostly organic, local farms when we can (which is pretty often, esp in summer), grass fed when we can. Our kids totally eschew fast food and when we eat out it is very very high quality and often farm-to-fork. I've always had a propensity to gain weight, as does one of my three children (10,11,13). As a result I am very strict about snack foods, sweet or salty. Plus frankly if you are going organic that cuts out a lot of the middle of the grocery strore anyway. All that said, I believe, and behavioral research supports this, that overeating can be a crime of convenience. You eat more when food is served family style on the table, with a serving bowl in front of you, then if you were given a portion on your plate and need to get up to get more. You eat more fruit if it is in a big pretty bowl on the table. If you were a store, you would market food by making it easy to see and get to. If you are at home, you can suppress eating by keeping food out of sight. My last home was a very formal older home and the kitchen was isolated. My current home is more casual and the kitchen is not open, but it is sort of a hub off of which many other rooms and hallways flow. At our lakehouse, we have a kitchen/great room. If the weather is such that we are not outside, we are usually in this room. I witness everyone snack and nosh more, because we are actually, in a sense, living in the kitchen. I have a comfy chair I like to read in, and it faces the pantry. Even though all i see is the cherry cabinet, I know what's in it! And I want it! (Come to think of it, I am moving that chair when we go up this weekend!). Anyway, we have been able to test the null hypothesis and in my family, at least, an open kitchen means more frequent snacks. We are in the process of buying a beachhouse and I can promise you it will have a closed kitchen! PS Marcolo --- how sweet of you to remember! I read the article in the NYT a few days ago and just rolled my eyes! I think it is so so true. BTW my DH loved "goy 'em up". : )...See MoreInteresting article in NY Times about CryptoWall

Comments (22)Sindely ... you don't have to go to the bad neighborhood ... it sends hit men out to find you. ============= http://www.proofpoint.com/threatinsight/posts/malware-in-ad-networks-infects-visitors-and-jeopardizes-brands.php "Malvertising attacks use online advertising channels to infiltrate malware into the computers of unsuspecting users by embedding malicious code within legitimate advertisements on trusted websites. " "Without having to click on anything, visitors to the impacted websites may be stealthily infected with the CryptoWall 2.0 ransomware. Using Adobe Flash, the malvertisements silently âÂÂpull inâ malicious exploits from the FlashPack Exploit Kit. The exploits attack a vulnerability in the end-usersâ browser and install CryptoWall 2.0 on end-usersâ computers." Here's a partial list of known infested sites - (biased because it was an Aussie research group) - which have since been cleaned up. Yahoo! Finance, Fantasy and Sports (yahoo.com, Global 4, US 4), AOL (realestate.aol.com, US 37, Global 119), The Atlantic ( theatlantic.com, US 386, Global 1,206), 9GAG (9gag.com, US 528, Global 201,), match.com (US 203, Global 631), The Sydney Morning Herald (www.smh.com.au, Australia 13, Global 780), realestate.com.au (Australia 17, Global 1,656), The Age (theage.com.au, Australia 34), stuff.co.nz (New Zealand 9), societe.com (France 54, Global 1,649), Dumpert (dumpert.nl, Netherlands 24), Flirchi (flirchi.com, India 106, Global 1,129), Weatherzone Australia (weatherzone.com.au, Australia 111), Brisbane Times (brisbanebrisbanetimes.com.au, Australia 183), RSVP (rsvp.com.au, Australia 351), The Canberra Times (canberratimes.com.au, Australia 403), Time Out (US 1,145, Global 1,816), The Beacon-News (beaconnews.suntimes.com, US 1,178), Merca2.0 (merca20.com, Mexico 229), clicccar.com (Japan 1,124), iPhone for Hong Kong (iphone4hongkong.com, HK 112), Noticias Argentinas (noticiasargentinas.com, Argentina 784)...See MoreBack to the (future) NXR

Comments (26)I think your existing kitchen layout and your wife have already nixed a "proper" hood if you mean one with an optimal design. As has been said elsewhere here, we work with the kitchens we have. A lot of us have to work with less than optimal hood choices and that is just how it is. Just because you can't have the best possible thing doesn't mean you cannot have something adequate. For searching on hoods and MUA, our resident ventilation guru is kaseki. If you want advice on "optimal" above a 30-inch NXR, then you want something that is: 27" inches deep (front to back) for best coverage and capture above all four burners; 36" wide (side to side) to capture cooking effluent that might go a bit sidewise because of turbulence; and a canopy tall enough (probably 18" high at least) to provide good containment. Sound like a no-go for you? Rules of thumb for CFM? These take no account of hood design. (ETA -- I only saw Eric's post after I uploaded this, so I apologize for the duplication). For electric stoves (including induction) and less-expensive standard brand gas ranges and cooktops, the rule of thumb is 100 CFM per linear foot of stovetop. For a 30-inch wide stove --- that is 2½ linear feet --- the rule of thumb is 100 CFM x 2.5 ft = 250 CFM. For pro-style gas cooktops and stoves (including the NXR) the rule of thumb is 1 CFM per 100 btu of burner ratings. With the NXR having 4 burners of 15k each, that translates to 600 CFM. You mentioned reading Nunya's NXR postings from two and three years ago. I'm guessing you've seen the discussions and photos about using 400 CFM OTR/MW units over NXR ranges. We work with the budgets and kitchens and preferences we have. (Verdict on OTRS? Adequate for those folks' cooking but not optimal and maybe requiring opened windows sometimes.) My own old-house kitchen is such that I only had room for a 650 CFM Zephyr Cyclone. It has a flat bottom (as opposed to a canopy), is only 5½" tall (so no room for much canopy anyway) and only 23" front to back (but, at least, that is far enough back that I'm not bumping into it while cooking.) At least cabinets were high enough to allow for a 36" wide unit, though. What this gives me is: tolerable for heat removal from the room (better than nothing for the person standing at the stove but fine for the rest of the kitchen); it collects and fllters much the greasy effluent (I clean the traps regularly and do not have to clean grease off the cabinetry and counters very often). Mostly adequate on steam collection. (I also tend to put the big pots in the back where the collection/pick-up is a bit better,) Seriously suboptimal for anything smokey even with the windows opened and the ceiling fan helping out. (I don't do heavy-duty wokking and blackened whatevers and serious grilling get done outdoors.) Note, whatever you get, you will want a smooth and hard-sufaced, easily cleaned backsplash because you will get a bunch of goo back there. It needs to go all the way up to the bottom of the hood (if not behind it). I had our local glass shop fabricate a tempered glass plate for me and it is very easy to clean. Other options include a metal plate (a lot of folks like stainless steel) and tile (specifically something with a hard glossy surface as on subway or glass tiles.) Quite apart from whether you have code requirements, you want to pay attention to MUA issues. Its the laws of physics that are important here, not just regulatory requirements. Depending on your house's design and construction, MUA can be simple and cheap or complicated and expensive. With my gas water heater and furnace in the basement, well away from the kitchen range hood, I was able to build MUA systems for them for very little money (less than $20 each). I have had no problems with backdrafting from the range hood. YMMV....See MorePaw print (and everyone else) re: NY Times series on disabilities

Comments (5)Go to the site or page you want to link to, and copy the top bar on your page to save the address. Copy by left clicking the address, and right clicking and choosing 'save' from the menu you see. Then, directly below each post when you click 'write a comment' in GW you will see a series of icons including on the far right a 'link' with a little picture of a chain link. Left click on the 'link' icon, and in the lower area that says 'web address' then right click, and click on the menu item that says 'paste'. Then go to the upper area and put in whatever title you want for your link, such as 'New York Times Article'. Then click on 'insert' to put it into your post....See Morejwvideo

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agododge59

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agodeeageaux

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agokaseki

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agojwvideo

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agoGooster

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agokksmama

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agododge59

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agocookncarpenter

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agojwvideo

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agokaseki

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agogigelus2k13

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agokksmama

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agokitchendetective

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agorococogurl

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agoFori

10 years agolast modified: 9 years agokksmama

10 years agolast modified: 9 years ago

Related Stories

MOST POPULARA First-Time Buyer’s Guide to Home Maintenance

Take care of these tasks to avoid major home hassles, inefficiencies or unsightliness down the road

Full Story

EARTH DAYHow to Build a Greener Driveway

Install a permeable driveway to keep pollutants out of water sources and groundwater levels balanced

Full Story

HOMES AROUND THE WORLDThe Kitchen of Tomorrow Is Already Here

A new Houzz survey reveals global kitchen trends with staying power

Full Story

KITCHEN DESIGNKitchen of the Week: Great for the Chefs, Friendly to the Family

With a large island, a butler’s pantry, wine storage and more, this New York kitchen appeals to everyone in the house

Full Story

REMODELING GUIDESWisdom to Help Your Relationship Survive a Remodel

Spend less time patching up partnerships and more time spackling and sanding with this insight from a Houzz remodeling survey

Full Story

KITCHEN CABINETS8 Cabinetry Details to Create Custom Kitchen Style

Take a basic kitchen up a notch with decorative add-ons that give cabinets a high-end look

Full Story

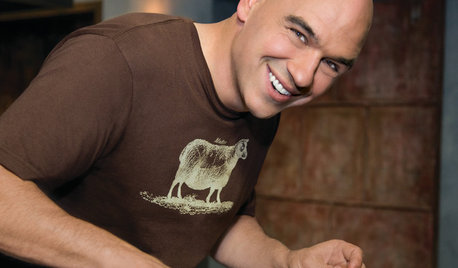

TASTEMAKERSPro Chefs Dish on Kitchens: Michael Symon Shares His Tastes

What does an Iron Chef go for in kitchen layout, appliances and lighting? Find out here

Full Story

KITCHEN DESIGNHow to Choose and Use Ecofriendly Kitchen Appliances

Inefficient kitchen appliances waste energy and money. Here's how to pick and use appliances wisely

Full Story

KITCHEN APPLIANCESWhat to Consider When Adding a Range Hood

Get to know the types, styles and why you may want to skip a hood altogether

Full Story

HEALTHY HOMEDetox Your Kitchen for the Healthiest Cooking

Maybe you buy organic or even grow your own. But if your kitchen is toxic, you're only halfway to healthy

Full Story

kksmama