ID needed - tall, yellow button flowers

SnailLover (MI - zone 5a)

9 years ago

Related Stories

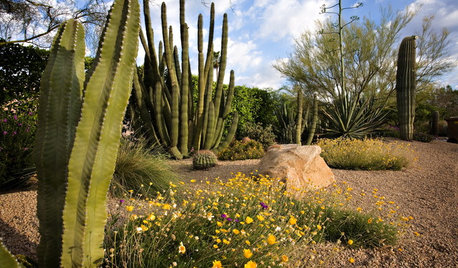

SOUTHWEST GARDENINGTall Cactuses Bring Drama to Southwestern Gardens

See how 5 columnar cactuses add a striking design element to warm-weather gardens, courtyards and entries

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESHartweg’s Sundrops Blankets Southwestern Landscapes in Yellow

The vivid flowers of Calylophus hartwegii add sunny color to drought-tolerant gardens from spring through fall

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDES5 Favorite Yellow Roses for a Joyful Garden

Make 'cheery' the name of your garden game when you order your roses sunny side up

Full Story

KITCHEN SINKSEverything You Need to Know About Farmhouse Sinks

They’re charming, homey, durable, elegant, functional and nostalgic. Those are just a few of the reasons they’re so popular

Full Story

Ideabook 911: My House Needs a Facelift!

Houzz Member Gets Ideas for Sprucing Up This Deck and Garage

Full Story

LIFEDecluttering — How to Get the Help You Need

Don't worry if you can't shed stuff and organize alone; help is at your disposal

Full Story

FLOWERSKeep Your Garden on Point With Spikes of Purple

Tall purple blooms bridge color gaps, contrast round flower forms and make for intriguing masses in the landscape

Full Story

GARDENING GUIDESGreat Design Plant: Yellow Bells, a Screening Queen

With its large size and copious golden flowers, this shrub can cover walls or screen unsightly views with ease

Full Story

COLORDreaming in Color: 8 Eye-Opening Yellow Bedrooms

Start your day energized and cheerful with bedroom hues that sing of sunshine or golden fields

Full Story

EVENTSReport From Italy: Mustard Yellow, Hidden Kitchens and More

See what our team in Italy discovered at Salone del Mobile 2016. Which new design idea speaks to you?

Full Story

kayjones

Iris GW

Related Discussions

Need ID for tall purple flowering weed (?)

Q

Gorgeous yellow flowering tree with large flowers needs an ID.

Q

Yellow button-like flowers?

Q

Yellow Flower ID needed S.E. MI z5

Q

SnailLover (MI - zone 5a)Original Author

wisconsitom

Iris GW

dbarron

SnailLover (MI - zone 5a)Original Author

dbarron

lycopus

Lynda Waldrep

wisconsitom

dbarron

wisconsitom

lycopus

wisconsitom

lycopus

wisconsitom

lycopus

Naturedeva

jaynine

dandy_line (Z3b N Cent Mn)

wisconsitom

Lynda Waldrep

wisconsitom

WoodsTea 6a MO

wisconsitom