Why Societies Collapse

althea_gw

19 years ago

Related Stories

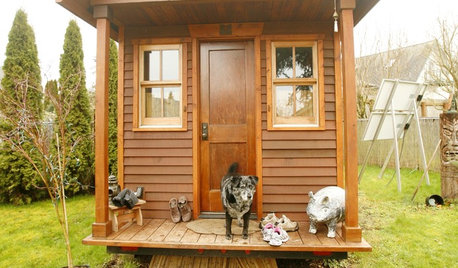

SMALL SPACESLife Lessons From 10 Years of Living in 84 Square Feet

Dee Williams was looking for a richer life. She found it by moving into a very tiny house

Full Story

EARTH DAYHow to Design a Garden for Native Bees

Create a garden that not only looks beautiful but also nurtures native bees — and helps other wildlife in the process

Full Story

PETSWe Want to See the Most Creative Pet Spaces in the World

Houzz is seeking pet-friendly designs from around the globe. Get out your camera and post your photos now!

Full Story

THE HARDWORKING HOME8 Laundry Room Ideas to Watch For This Year

The Hardworking Home: A look at the most popular laundry photos in 2014 hints that dog beds, drying racks and stackable units will be key

Full Story

FARM YOUR YARDHello, Honey: Beekeeping Anywhere for Fun, Food and Good Deeds

We need pollinators, and they increasingly need us too. Here, why and how to be a bee friend

Full Story

KITCHEN CABINETSChoosing New Cabinets? Here’s What to Know Before You Shop

Get the scoop on kitchen and bathroom cabinet materials and construction methods to understand your options

Full Story

TASTEMAKERSNew Series to Give a Glimpse of Life ‘Unplugged’

See what happens when city dwellers relocate to off-the-grid homes in a new show premiering July 29. Tell us: Could you pack up urban life?

Full Story

BUDGETING YOUR PROJECTConstruction Contracts: What Are General Conditions?

Here’s what you should know about these behind-the-scenes costs and why your contractor bills for them

Full Story

ORGANIZING8 Incredibly Clever Organizing Tricks

A tension rod under the sink; wire and nails in the closet ... these storage and organizing ideas are budget friendly to the max

Full Story

LAUNDRY ROOMSKey Measurements for a Dream Laundry Room

Get the layout dimensions that will help you wash and fold — and maybe do much more — comfortably and efficiently

Full StorySponsored

althea_gwOriginal Author

ericwi

Related Discussions

Article on Colony Collapse Disorder

Q

Collapse by Jared Diamond

Q

repair my collapsed closet rods

Q

1874 stone house mysteriously collapses.

Q

steve2416

ericwi

Monte_ND_Z3

marshallz10

vgkg Z-7 Va

althea_gwOriginal Author

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

kingturtle

marshallz10

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

marshallz10

althea_gwOriginal Author

pnbrown

marshallz10

kingturtle

pnbrown

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

pnbrown

kingturtle

marshallz10

wayne_5 zone 6a Central Indiana

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

althea_gwOriginal Author

pnbrown

kingturtle

althea_gwOriginal Author

kingturtle

wayne_5 zone 6a Central Indiana